18 min read

Technology has a significant impact on today's society.

The Ethics of Influence:

Unmasking Tech's Dance with Society's Psyche

In today's rapidly evolving digital era, the internet has become an integral part of everyday life, especially among the youth. However, along with this growing digital presence, concerns arise regarding the potential negative effects of excessive online activity, including the phenomenon of e-addictions. This term, though, sparks debates and controversies within the scientific community. Some researchers deem the use of the term "addiction" inappropriate when it comes to the internet, reserving it for substance addictions like alcohol, nicotine, or drugs. Conversely, others indicate that internet addiction can fall within the broader category of behavioral addictions, encompassing activities such as gambling (Majchrzak, Ogińska-Bulik, 2010).

It's worth noting that new forms of addiction, such as internet, gaming, or gambling addiction, share similar neurobiological mechanisms, including the role of the neurotransmitter dopamine. In the context of this discourse, the stance of the World Health Organization is significant. In its new disease classification ICD-11, effective since 2022, both gaming addiction and gambling addiction have been recognized as health issues. This underscores the growing need for understanding and intervening in the realm of e-addictions.

Studies conducted in the context of Poland shed light on the scale of this phenomenon. "Uzależnienia od e-czynności wśród młodzieży" project, employing the MAWI questionnaire (Styśko-Kunkowska, Wąsowicz, 2014), revealed that nearly 15% of surveyed adolescents aged 13-19 exhibit a high risk of e-addiction. This issue particularly affects young males and students in junior high and technical schools, with 25.7% and 21.7% respectively showing signs of e-addiction susceptibility.

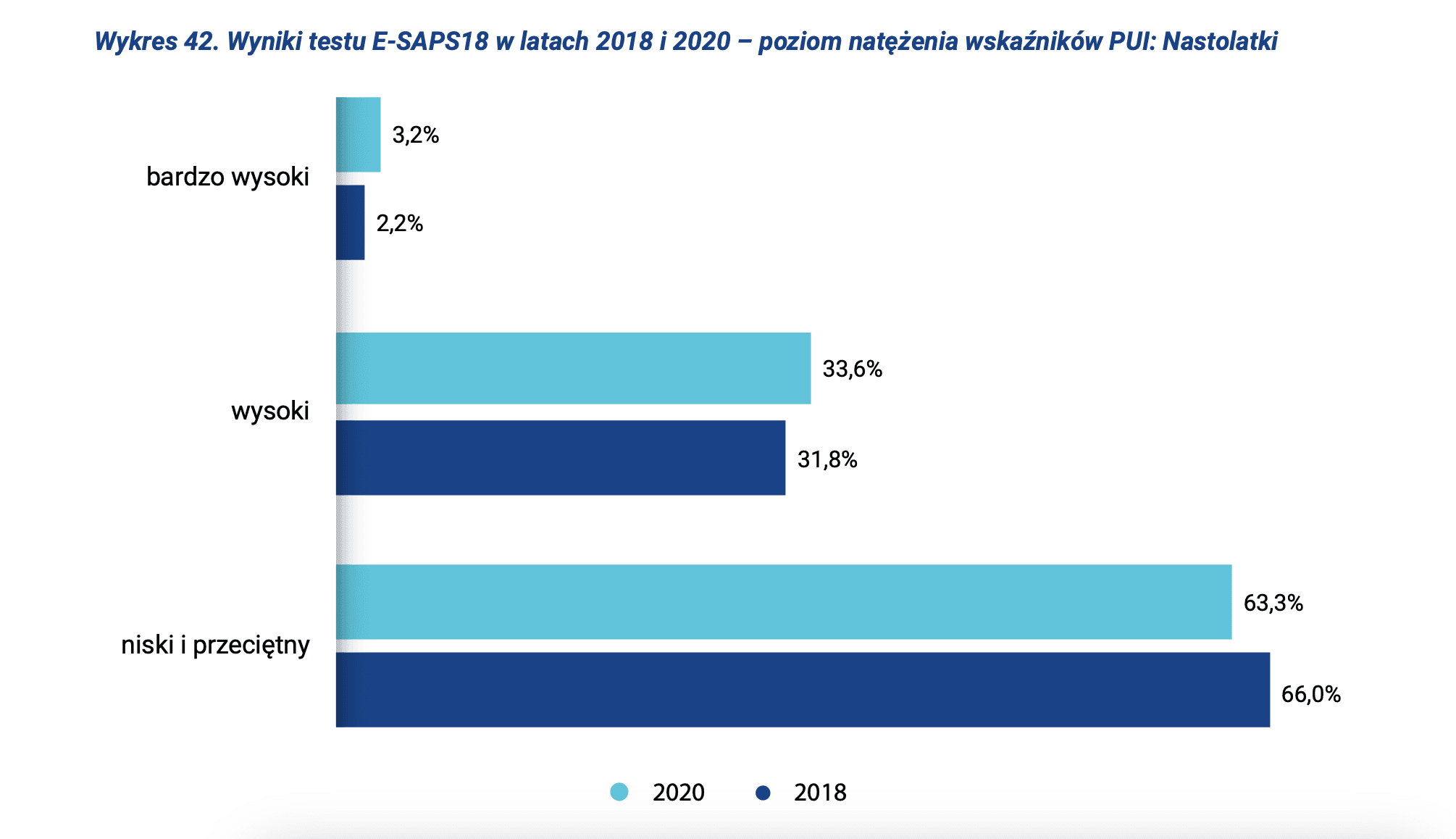

Based on the 2018-2020 E-SAPS18 test results, problematic internet use increased, mostly falling within low to moderate levels, with around one-third displaying moderate levels and over 3% indicating a very high level in 2020.

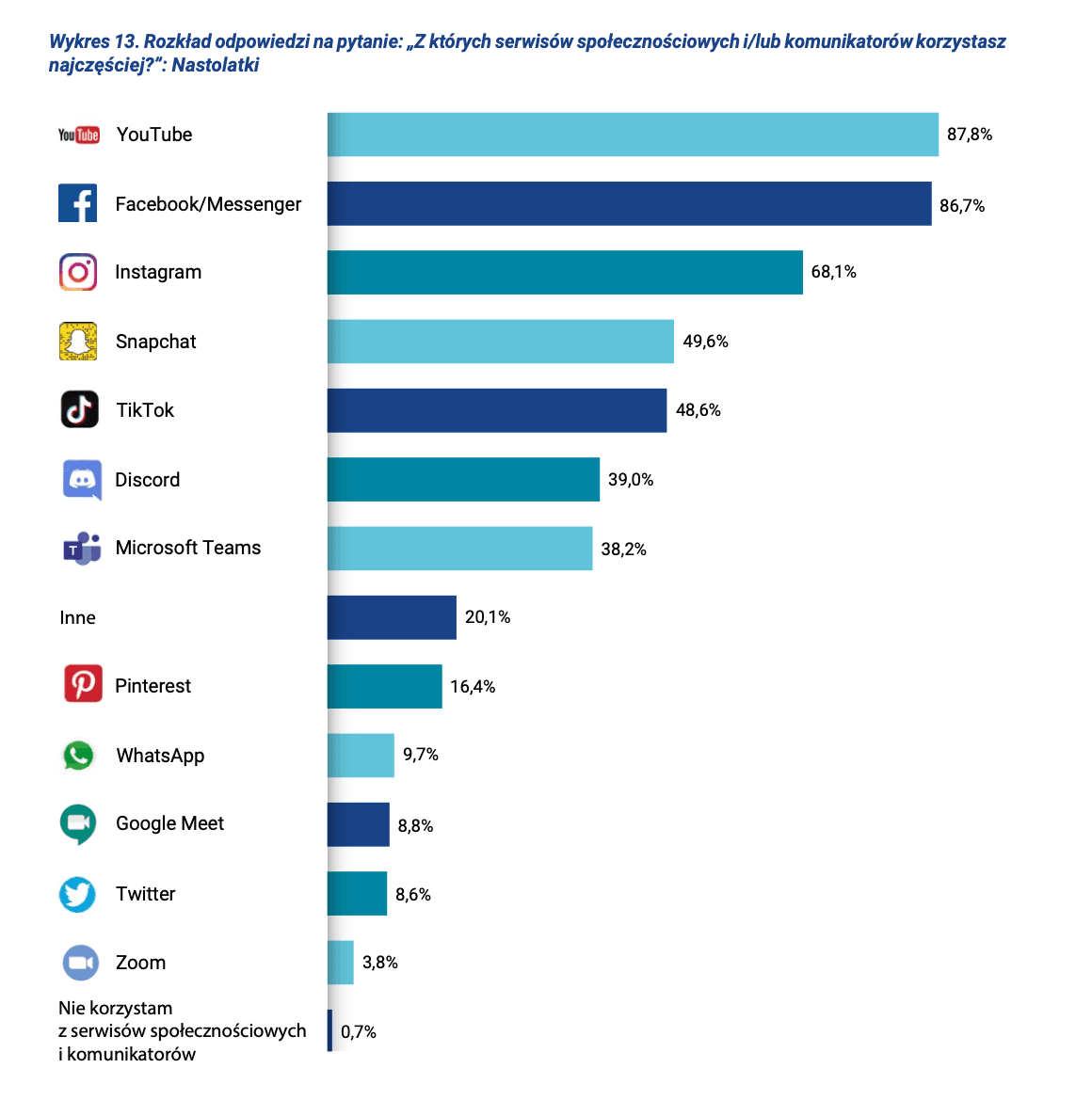

Distribution of responses to the question: "Which social media platforms and/or messengers do you use most frequently?" among teenagers.(1)

When analyzing the symptoms of Problematic Internet Use (PUI), it's apparent that adolescents often experience behaviors such as exceeding planned online time, using the internet to improve mood, and feeling irritable when denied internet access. The "Nastolatki 3.0" study corroborates these symptoms while also indicating that young people attempt to limit their internet usage, though not always with success.

However, what merits special attention is the role of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the context of e-addictions. Research suggests that online activities such as browsing social media, engaging in online gambling, or making online purchases can trigger dopamine release in the brain. This process can reinforce and solidify behaviors associated with e-addiction. The issue is complex. In this article, I will focus on the role of dopamine in shaping habits within digital products.

Understanding Dopamine: The Neurotransmitter Responsible for Pleasure and Reward

The matter is intricate, but my aim here is to center on how dopamine contributes to the development of addiction to digital products.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter in the brain responsible for feelings of pleasure and reward. In the context of this text, it is a pivotal factor in the mechanisms of manipulation and habit formation within digital technology. It is a substance that drives our behaviors and can be harnessed both negatively and positively in the design of digital products.

In the 1950s and 1960s, scientists James Olds and Peter Milner conducted an experiment. They placed mice in a cage with access to a button that, when pressed, triggered electrical brain stimulation, influencing dopamine release and inducing pleasurable sensations. The mice swiftly discovered that pressing the button brought about pleasant feelings, leading them to engage in this action obsessively. In doing so, they disregarded basic needs such as eating and drinking, ultimately experiencing exhaustion and death due to the neglect of these fundamental requirements.

The purpose of this experiment was to explore the effects of brain stimulation and its impact on animal behavior. It is frequently cited as an illustration of the adverse consequences of excessive activation of the reward system and the over-release of dopamine in the brain.

Dopamine affects, among other things:

- MOTIVATION

Dopamine deficiency is characterized by decreased motivation and reluctance to perform any activities. An excess of dopamine can result in a propensity for risky behaviors.2

- MEMORY

A dopamine deficiency leads to a deterioration of memory, especially working memory.3

On the other hand, an excess of dopamine can be associated with excessive stimulation of the reward center and neurons linked to working memory. As a result, misinterpreting situations and retaining everything can lead to chaos in the central nervous system.4

- CONCENTRATION

A dopamine deficiency leads to a decrease in concentration levels. When such a situation persists in the body over an extended period, it can result in the development of attention deficit disorder (ADD).5

- INTERPERSONAL COMMUNICATION

A dopamine deficiency is associated with phobia and social anxiety.6

An excess of dopamine leads to manic disorders and bipolar affective disorders. It can also be a cause of an excessive desire to control others, sometimes resulting in a propensity for violence. 7

The Role of the Dopamine Neurotransmitter in Habit Formation and Addictions

"The Hook Model" is a theory by Nir Eyal that describes a strategy for creating products and services aimed at attracting users through a cycle called the "hook." This process focuses on keeping users engaged and fostering addiction to the product or service.

The Hook Model, source: Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal, 2014, page 11

Trigger: It's a stimulus that initiates user behavior, acting like a spark. It can be external or internal.

Action: It's the behavior the user undertakes in response to the trigger. This could be a click, scroll, input, etc.

Reward: It's what the user receives after performing the action. It could be information, entertainment, satisfaction, or anything valuable to the user.

Investment: It's the stage where the user puts something into the product or service, such as time, data, effort, to enhance future experiences. This investment increases the likelihood of repeating the Hook cycle in the future.8

In young minds, these processes operate to a greater extent because the brain region associated with decision control and dopamine regulation, the substance responsible for generating feelings of pleasure, only matures around the age of twenty. During this time, the dopaminergic system, which influences pleasure and motivation, is already active from around the age of twelve. That's why adolescents are more susceptible to impulsive reactions, reinforced by using various applications or games that impact dopamine release and consequently affect their emotions. 9

Nothing personal, just business.

Here's the concise formula of today's addiction: click, scroll, like – while behind the scenes, someone collects data, displays ads, profits grow, and power consolidates. It's the worst-kept secret of modern digital success. Applications don't captivate us by chance – they're programmed to make our brains dance to the rhythm of one molecule: dopamine. This pleasure neurotransmitter triggers motivation and can ensnare us in addictions. A virtual cycle where the passion for manipulation weaves into a picture of dollars, data, and control.

- Candy Crush: the dopamine-fueled reward machine

At its core, this app has a unique mission: to entertain us for as long as possible and tempt us into buying various bonuses. It's a bit like stepping into a colorful world where the rules are set by us, the players, and these rules become the ultimate path to victory. But in this case, it's a game with our senses and emotions.

During the creation of this virtual entertainment, creators decided to delve into Gestalt philosophy. Doesn't that sound mysterious? It's the philosophy that tells us our brain excels at recognizing shapes and forms based on principles of proximity and similarity. The same principles that guide interface design and image composition now find a place in our play.

The beginning of the game is like the first step into an unknown realm. That's when you experience what's known as "beginner's luck." It's the moment when coins jingle in the witcher's pocket, and your ego blooms like a beautiful rose. All to make you feel irreplaceable, to make you know you're the master. It's not just psychology – physiology has a say here too. Compliments, those little dots on the screen that please the eye and soul, activate the brain region responsible for pleasure, releasing that magical substance known as dopamine. And those visual and auditory effects that accompany your gameplay? They're like "micro-reactions," tiny needles stimulating the dopaminergic system, administering doses of emotion and satisfaction.

From behind the scenes emerges the theory of flow, created by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. No, it's not some abstract philosophy, but rather a set of thoughts about the relationship between the challenge a task presents and our skills. They interact in perfect balance, like tightrope walkers in a circus. The game shouldn't be too easy or too hard; it's designed to grip us, draw us in, and transport us to a state where difficulties and efforts become irrelevant. All for our immersion, for the sense that we're part of this virtual reality.

- Instagram: The Illusion of Social Validation

We swipe our finger across the screen, scrolling through an endless stream of beautiful images. Each click is another step into the mysterious world B.J. Fogg, a behavioral psychologist and researcher at Stanford University, talks about in his persuasion psychology classes, attended by Kevin Systrom (one of Instagram's founders). He has a theory: every action we take has three key elements - motivation, ability to act, and what we call a "trigger". On Instagram, this trigger tugs at us, introduces a sense of unease, a feeling that something amazing is just around the corner, but we must act now not to miss it.

Of course, the ability to act seems commonplace today. Filters and image editors enchant us, creating a magical realm where even the simplest photo can look like a work of art. Anyone can be an artist, sketching beauty on their smartphone screen. But does that truly motivate us to act? Does it suffice to bring those plans and goals to life?

Yet, motivation takes a different shape on Instagram. It's less about artistic ambitions and more about the desire to be seen, appreciated, to showcase our world to the world. After all, why would we capture that perfectly styled coffee shop if not to share it with others? A mountain's peak photo without likes seems devoid of meaning. To us, it's not just a simple post; it's our heart and soul encapsulated in pixels.

Social validation is, at its core, a fundamental human need – an integral component of our social nature. Belonging to a group gives us a sense of value and security. And Instagram? That's where we can attain that sought-after validation, assess our worth through likes and comments.

Each click triggers a bit of dopamine in our brain – the substance that gives us that pleasant feeling of fulfillment and satisfaction. It's like receiving a small, electronic dose of happiness every time our photo is appreciated. This feeling fuels our desire for even more activity in this digital playground.

Instagram, this virtual marketplace of validation, is where gaining likes has become our currency. It's the marketplace where each of us sells our life in the form of beautiful frames. Is this aligned with our desire for validation? Is it worth it? We must answer these questions amidst the array of filters, likes, and our internal need to be seen.

- Uber: The Mirage of Choice

In a world brimming with choices, guiding people without imposition is like leading them toward the light without pushing them blindly. Cass Sunstein, a lawyer and philosopher, introduced the concept of "nudges", subtle prompts that steer us in the "right direction". It's like gentle whispering that allows us to believe we're making choices, while decisions are already made for us. Viewed through a technological lens, one can't overlook the autoplay feature. We've all caught ourselves wandering through episode after episode of a series for hours, unaware that the choice was lost long ago. It's as if a mysterious hand turned the key and set us on a divided path without our consent. It appears convenient, but where is our power of choice?

A similar mechanism is the quantitative goal - a strange beast that presents us with a seemingly "good" proposition. Our simple minds perceive it as a guarantee of success and efficiency. It seems like the answer – our best way to earn. As a result, we reportedly accept one more ride at the end of the day, even if we're on the brink of exhaustion.

But that's not all. Uber, leveraging psychological tricks, introduced badges that are as valuable as broken envelopes. Great music, a sparkling car, an exceptional guide, or a steering master – like decorations on a cake, they tantalize our psyche. We can be "better", attain something extraordinary, and above all, experience a touch of dopamine-induced pleasure. This allure encourages us to be better, to achieve this symbolic distinction.

Yes, we have a choice. But do we really? We often find ourselves following directions subtly indicated by nudges. It's like wandering in a maze of choices, guided by nudges that lead us toward bright lights, not necessarily aligned with our will. Is it still our decision, or are we ensnared in an intriguing web of suggestions? The answer lies in the elusive balance between choice and guidance.

- Facebook - Like to Survive

In today's online world, friendship has become the central theme of social interactions. And Facebook? It's like a colossal playground for our digital relationships. Why does this work so well? The answer might lie in Dale Carnegie's book "How to Win Friends and Influence People," where the key to friendship is a smile, attentive listening, and showing genuine interest in others. Doesn't that resemble behaviors on Facebook?

The rule of reciprocity - this is the magic of the social platform. It's like an invisible force compelling us to like, so that we, in turn, can be appreciated. Clicking "like" is our response to the craving for social interaction, the need for connection. We can't forget that in the evolution of history, friendship was an adaptive advantage - it increased our chances of survival, aided in defense, and enabled cooperation.

That's why we like, comment, and share - it's our tool for visibility, for participating in the community. For our brain, it's a reward - we receive a dose of dopamine when our activity meets a reaction. It forms a cyclical pattern - we act in a way to gain acceptance, and simultaneously, we receive it.

Does the number of friends matter? Even if we have only a few, posting brings us joy akin to conversations with loved ones. It's an illusion of interaction that feeds into our reward system. Because behind each "like" isn't just a click, but confirmation of our value in the eyes of others.

Charles Darwin, the eminent researcher of facial expressions, categorized them into 6 universal emotions. Thanks to these, we have the ability to express joy, surprise, sadness, anger, disgust, and fear. And Facebook? It harnesses these to create "reactions" that further connect us emotionally. It's like the language of emotions, conveying more than a thousand words.

Facebook - it's not merely a platform, but a labyrinth of our interactions. What might seem like a simple "like" to some is validation of existence and visibility to others. It's akin to a contemporary version of "winning friends and influencing people". Though not always an ideal reflection of real-world relationships, it remains a spectacular spectacle where each of us plays a role.

- Psychological Tricks of Snapchat: How Dopamine and Streaks Create a Daily Addictive Ritual

The more we engage with something, the more value we attribute to it. This hidden principle doesn't just apply to furniture stores, but also to our daily lives in the digital realm. After all, don't we feel connected to what we create ourselves? In the world of digital relationships, it's no different. Your personalized video, received as a reward, hits right at the heart - a shot of dopamine named "reward".

Admit it, you've felt it before - swiping your finger across the screen to see the next snap. It's like uncovering a mysterious present, with each photo or video a small surprise feeding our reward system. Marcel Mauss, an ethnologist, claimed that gift-giving is universal. Could it be that every second spent on social media is accompanied by the spirit of a modern-day gift? Maybe that's the case - a gift that gives us a sense of being seen and appreciated.

However, as is often the case, there's another side to the coin. A "like" - our digital calling card - carries the weight of social pressure. The absence of a like is read as a sign of rejection, a blow to our self-esteem. It's not just a virtual matter - our brain associates rejection with physical pain, as if we've been wounded. It's just a click, right? But for us, it's much more - a sign that our social worth has risen or fallen, which is why Snapchat avoids using this feature.

Then there's Streak - that cunning option counting the consecutive days we maintain contact with someone. It's like a fidelity counter that grows in strength, turning us into loyal friends. Isn't it fascinating how such a simple feature can become such a powerful psychological tool? Every flame on the streak counter is a dopamine boost, a reward for our brain. The more days pass, the harder it is to let go, the more pressure to not give up.

It's the IKEA effect in its digital form - creating our own value, attachment to interactions, the illusion of a gift with every click. Isn't it intriguing how something seemingly virtual can deeply influence our emotions? Thanks to this, we have friends on the screen, even if it's often just one click away from our fingertips.

Shaping Habits and Creator Responsibility: The Ethics of Technological Influence on Society

In the era of technology, where minds are shaped by subtle impulses and sophisticated strategies, the question of its ethical implications arises. After delving into the pattern of habit formation and the awareness of the impact they have on our psyche, a dilemma emerges - how to wield this knowledge responsibly? Is the Hook Model, which has become the key to creating addictive technologies, merely a tool for manipulation?

While reading the book, one might start feeling uneasy, wondering if such actions are morally sound. The Hook Model, which alters our habits and behaviors, carries immense power but should be used with caution. Creating habits is not just psychology; it's also a moral responsibility of creators. After all, we're all in the persuasion business - creating products to guide people towards our desires. Even if we don't explicitly state it, deep down, we hope every user becomes addicted to our solutions. In this invisible competition for our attention, technologies accompany us from dawn till dusk, shaping a new world of social interactions. When we contemplate these mechanisms further, the question of ethical boundaries arises. Can what appears as manipulation also serve as a beneficial tool? Weight Watchers, for instance, sets dietary rules, yet it doesn't evoke the same outrage as other forms of manipulation. Does our moral scale lag behind modern technologies? In an age of ubiquitous internet access and data transmission, there's a need to create societal "antibodies against addiction."

All of this leads us to question the role of those who create these technologies. Do corporations introducing addictive technologies realize the consequences of their actions? Habit creation is both a force for good and a potential misused power. In today's world, where we succumb to illusion, it's worth pondering our engagement in this game. Perhaps it's time for a new ethical vision of technology creation that not only brings joy but also enhances our awareness, making us more responsible digital citizens.

As designers and creators of digital products, we bear immense responsibility for how our solutions impact society. Reflecting on the consequences of our actions is crucial. Mechanisms that foster addiction can also be harnessed positively. Applications that influence our well-being, encourage learning, and shape desirable habits are just a few examples. It's like a knife that can be used to prepare a healthy meal or inflict wounds. Technology is a tool, and its intentions depend on its creators. It's important to remember that we can harness these mechanisms to craft products that not only engage but also bring value to society, supporting healthy behaviors and personal growth.

1 NASK, Nastolatki 3.0 - Report from a Nationwide Study of Students, Warsaw 2021

2 Stefano I. Di Domenico, and Richard M. Ryan, The Emerging Neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation: A New Frontier in Self-Determination Research, Front Hum Neurosci., 2017

3 González-Burgos, Feria-Velasco A., Serotonin/dopamine interaction in memory formation, Prog Brain Res., 2008

4 Shelly B. Flagel, Jeremy J. Clark, Terry E. Robinson, Leah Mayo, Alayna Czuj, Ingo Willuhn, Christina A. Akers, Sarah M. Clinton, Paul E. M. Phillips, and Huda Akil, A selective role for dopamine in reward learning, Nature, 2011

5 Nieoullon A., Dopamine and the regulation of cognition and attention., Prog neurobiol., 2002

Dreisbach G., Goschke T., How positive affect modulates cognitive control: reduced perseveration at the cost of increased distractibility, I Exp Psychol learn Mem Cogn., 2004 6 Colin G. DeYoung, Personality Neuroscience and the Biology of Traits, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2010

7 King RJ, Mefford IN, Wang C, Murchison A, Caligari EJ, Berger PA., CSF dopamine levels correlate with extraversion in depressed patients, Psychiatry Res., 1986

8 Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products, Nir Eyal, 2014

9 The Teen Brain: Still Under Construction, Jay N. Giedd, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2011

Share article

Joanna Bałdyga

UX Designer